My Middle-born Boy

My middle-born son, age fifteen, did not die on Wild Hay River last week.

He did not die there but he did go there on a canoe trip with his Scouting group. As they went along, the flotilla wound up in an unforeseen, dangerous flooded section of the river. I wasn’t there but I am told a couple of boys evacuating a nearby canoe accidentally capsized the boat my son, my husband, and another boy, only twelve years old, were in. All three of them were dumped into the river. The current was strong, rushing toward a large spruce log covered in spiky broken branches spanning the river from shore to shore. It was large and dense enough to obscure the view of what was on the other side of it. Beyond and beneath it, there would be more water, and maybe all hell.

In the water, the current divided my husband from the kids. He stood in deep, fast water on one bank, anchoring himself by holding onto slippery tree branches with his cut and bleeding hands, shouting out to the boys not go under the fallen tree but to try to grab onto it if they couldn’t get out of the water. Fighting to stay on his feet, he remained in the water, waiting to see if the boys would be able to stop themselves. If they couldn’t, he would let go and let the river push him after them—a bad but only hope. And that would be that.

The younger boy was closer to the opposite bank and strong and smart enough to grapple out of the water on his own. Our son was further in. He was leaning back against the current, digging into the rocks of the riverbed with his bare feet, his boots long gone. My son’s friends stood on the bank in shock. They watched him being pushed closer to the fallen log—a horrible, unknown. To them, the spiked log might have looked like a barrier in a video game—the kind that ends the level and uses up a life.

I have a vivid imagination. It’s an important part of my trade but it’s also awful. In that imagination, I can see a curly, blond, drenched head pushed along the surface of a rough, glacial river. I can see a little white face with eyes just like my grandfather’s in it, staring up out of the water at jagged spikes.

As the log came within his reach, my son rose up out of the water, moving higher and faster than anyone watching thought was possible. He took hold of the tree’s broken branches and stopped himself from being pushed underneath it. “I’m okay,” he told himself, and hand-over-hand, without the help of anyone he could see, he pulled himself out of the river. Safe, he turned to see his father give him a thumbs up and climb out of the river on the opposite shore.

Earlier this year, I had been invited to the Scouting committee meetings where the trip was planned and I didn’t attend a single one. I wasn’t there asking if the river had been scouted yet this season. I wasn’t there to insist on it or to offer to strap on a can of bear spray and scout it myself. I didn’t do any of those things but I get to keep my son anyway. Do not underestimate my gratitude for the grace extended to parents who mess up.

Sure, many good things will come to my son from this experience. He learned it’s possible for him to rescue himself. The boy who was so unsure of his abilities he didn’t perfect riding a bike until he was eleven has now had the experience of reaching out and saving himself. He also lived through one of those tricky human paradoxes where difficulties placed in our paths (like the fallen tree) are often themselves the ways out of the difficulty. He got more perspective on what he is worth to his father, both when his dad stayed in the water until he was out, and when he saw his father safe on the bank advocating for a difficult portage, for not getting right back into the river even if it meant abandoning the canoes in the woods and reimbursing the Scout group for the loss of them out his government salary. Stuff is nothing, work is nothing, money is nothing. You, boy, are everything.

These are all good lessons—powerful lessons, the kinds of mishap-lessons that find all of us no matter how we live our lives. The world is dangerous and unpredictable for everyone. However, I don’t believe these lessons are the ones Scouting has in mind when it promises kids adventure. It’s a stodgy old Commonwealth institution, actually, one with waivers to sign and plenty of liability insurance. It offers character building in terms of well-organized food drives, and gaining confidence and competence by going into the wild to learn to traverse, navigate, build shelter, find and cook food, and stay safe. It’s about exploration, not exploits—understanding the immense power of the natural world, standing close enough to sense its awesome power, and then taking a respectful, sober step back into the preparations and planning that are our best chance for coming home. We will go back and we’ll do better next time.

Downstream on the Wild Hay River, the canoe my family had been in—the one that had capsized and washed away, upside down, under the fallen tree—was recovered. It was sitting upright and aground on a gravelly bar. In it was the bag containing my husband’s driver’s license, and one of our son’s hiking boots. Gone was my husband’s sloppy Scouter hat I had openly hated. So sloppy–here’s to its passing.

Earlier this year, Sistering was awarded Best Novel by the Association for Mormon Letters, an international community that’s been very kind and supportive of my work. They sent one of their best and brightest, Michael Austin, to do an email interview with me–the most Mormon and, interestingly, the least gender role fixated one I’ve ever done. The link to read it is

Earlier this year, Sistering was awarded Best Novel by the Association for Mormon Letters, an international community that’s been very kind and supportive of my work. They sent one of their best and brightest, Michael Austin, to do an email interview with me–the most Mormon and, interestingly, the least gender role fixated one I’ve ever done. The link to read it is ![20160708_120224[1]](https://jenniferquist.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/20160708_1202241.jpg?w=471&h=353)

![20160707_162819[1]](https://jenniferquist.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/20160707_1628191.jpg?w=209&h=279)

![20160710_213806[1]](https://jenniferquist.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/20160710_2138061.jpg?w=215&h=287)

![20160708_151405[1]](https://jenniferquist.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/20160708_1514051.jpg?w=235&h=313)

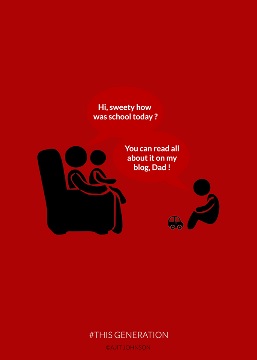

The generation in question isn’t the artist’s own cohort either. From what I can tell, he’s a salty old fella from the beginning of the Millennial spectrum. #THISGENERATION—the one harpooned in his simple red graphics—is that of my kids and current classmates.

The generation in question isn’t the artist’s own cohort either. From what I can tell, he’s a salty old fella from the beginning of the Millennial spectrum. #THISGENERATION—the one harpooned in his simple red graphics—is that of my kids and current classmates. Let’s pursue a methodical close reading of a few of the posters. In this one, #THISGENERATION is hassled for going somewhere private to take pictures of themselves to post in public. Sure, this is a situation that has and will continue to showcase a whole lot of terrible youthful judgment. But let’s hold our noses, take a page out of the gun lobby’s script, and remind ourselves that cameras don’t exploit people, people exploit people.

Let’s pursue a methodical close reading of a few of the posters. In this one, #THISGENERATION is hassled for going somewhere private to take pictures of themselves to post in public. Sure, this is a situation that has and will continue to showcase a whole lot of terrible youthful judgment. But let’s hold our noses, take a page out of the gun lobby’s script, and remind ourselves that cameras don’t exploit people, people exploit people.

but from older people. Most of us won’t commit to long, challenging gamer-ism so we play simple, free, throw-away games like Candy Crush. It’s mostly an old people game.

but from older people. Most of us won’t commit to long, challenging gamer-ism so we play simple, free, throw-away games like Candy Crush. It’s mostly an old people game. I was amused recently to read a twenty-year-old paper warning scholars they ought to take spoken literature (orature) more seriously since it was all #THISGENERATION was going to abide. In the early days of texting, a prominent Canadian author wrote a novel including a vision of the future where both written and spoken communication had morphed into flip-phone era texting shorthand. Of course, that hasn’t happened. #THISGENERATION doesn’t often use their phones as phones. When dealing with people at a distance, they prefer written over oral communication. A phone call means someone’s dead or in jail. #THISGENERATION has become extremely literate, plugging away on Tumblr writing heavy text posts about art and relationships and social justice, learning creative writing in epic style on fan fiction sites, while older adults quip away in 140 characters. No one reads and writes more than #THISGENERATION.

I was amused recently to read a twenty-year-old paper warning scholars they ought to take spoken literature (orature) more seriously since it was all #THISGENERATION was going to abide. In the early days of texting, a prominent Canadian author wrote a novel including a vision of the future where both written and spoken communication had morphed into flip-phone era texting shorthand. Of course, that hasn’t happened. #THISGENERATION doesn’t often use their phones as phones. When dealing with people at a distance, they prefer written over oral communication. A phone call means someone’s dead or in jail. #THISGENERATION has become extremely literate, plugging away on Tumblr writing heavy text posts about art and relationships and social justice, learning creative writing in epic style on fan fiction sites, while older adults quip away in 140 characters. No one reads and writes more than #THISGENERATION.