This is Jay Chou. He sings and plays piano and cello for me while I study.

I really should be studying for the grammar exam and the oral presentation I need to perform in finely articulated Chinese tomorrow. I have, I will. But first, some completely unproductive catharsis. I give you eight scary things you might not know about studying Chinese:

- Reading fancy Chinese characters – that’s the easy part. It’s a task of rote memorization which, while grueling, isn’t actually complicated and can be achieved to perfection. Who gets full marks on vocabulary tests? In my class, we all do.

- The hardest part of learning Chinese is understanding ANYTHING people are saying out loud. Even if we had ears perfectly tuned to “tones” — the prescribed accents Chinese speakers use, changing the pitches of their voices while pronouncing vowels — Chinese might still seem like a handful of short words that all sound pretty much the same. The language has an abundance of homophones. English has them too – words like meet, meat, and mete—but Chinese has many, many more. It’s a language with a “limited sound palette” which is a pretty way of saying that without a sound understanding of context, it’s impossible to tell one word from another without being able to see their written characters (though some of the characters look the same but are pronounced differently and have different meanings because even the easiest things are not easy here).

- It takes twice as many hours of instruction in Chinese than it does in ANY OTHER LANGUAGE offered at my large, world-class university to be considered an “intermediate” level student. And judging from myself, by “intermediate” level they must mean someone who still bursts into tears when being spoken to at normal conversational speed.

- There is no “It” as we Anglophones know it in Chinese. Yup, unless we’re talking about a pronoun for animals or other specific objects under certain circumstances only, there is no “It.” We can’t say “It’s raining” in Chinese. We can’t say “It seems like you’re frustrated.” Speaking Chinese is like a Monty Python skit that way. You know Monty Python, the quintessential ENGLISH sketch comedy troupe, who imagined nothing could be more linguistically nonsensical than speaking without ever saying “It.” Haha, welcome to China, ignorant old Pythons.

- The absence of “It” is just the beginning. Chinese also has no plurals as we know them, no capitalization, no verb declension. In all the materials I’ve ever seen meant to encourage students to choose Chinese, “simple grammar” is touted as a benefit. It’s faulty reasoning. English grammar isn’t simple. We don’t like simple grammar. We don’t trust it. We can’t handle it. We overthink it, tacking on superfluous prepositions and pronouns, getting hung up on details Chinese doesn’t care about while ignoring things it cares deeply about. For instance, if we’re using Chinese to describe someone in the middle of doing a task that can’t last for very long, we use different grammar than if we’re talking about someone in the middle of a task that can last a long time. Simple, right? Maybe, but the Anglos are all back at the beginning arguing about what the concept of “can’t last for very long” might actually mean. And the Chinese grammar that stands somewhere near the place of our dear English past tense – well, it seems scattered and piecemeal to us, chaotic, and as one professor famously says, just plain “evil.” So I don’t want to hear ONE MORE WORD about how Chinese grammar is simple.

- Studying Chinese brings a sense of contempt for the idea of studying other, less punishing languages. I admit it was not one of my finest hours when I scoffed at a bilingual friend, telling him that, especially here in Canada, “Reading French is like

Mynah birds, alien experts in mimicking human speech

grocery shopping. Reading Chinese is a super power.” Nice one, Jenny. Still, the idea that a foreign language could be spoken with some recognition just by sounding it out in letters we’ve known since we were babies, the idea that two languages might share cognates or at least words with the same roots that can be decoded if one is clever and knowledgeable of one’s mother tongue – all that comes completely apart for English speakers studying Chinese. We approach it like we’re mynah birds.

- It takes a whole community to learn Chinese. It’s not a task for Google Image searching tattoo enthusiasts or loners in dark basements watching Kung Fu movies with the subtitles turned off. Learning Chinese demands a mortification of the ego in every way. Lay down that pride. We sound like toddlers but we speak out loud in a crowded room anyway. We cry for help, rely on everyone, all our linguistic brothers and sisters at arms. Sure, all language classes include group work and partnerships. But in my many years of school, I’ve never seen anything like the camaraderie of a Chinese class.

- Chinese students – especially people from my Western and girlie demographic – need to be prepared to explain themselves. After all this ranting and venting we need to have answers for obvious questions about why we’re studying this language when there are more attainable languages much closer to home. What’s our problem? What happened to us? 怎么了?My reasons for choosing Chinese are complicated and idealistic. I still believe in them. But lately, I’ve taken to replying with, “What? Why’d I pick Chinese? Uh, who knows? It seems like a long time ago now…”

Anyways, sorry about the shouting. Thanks for reading. Enjoy your day. Listen to some Jay Chou music. As for me, as one of my fellow English-people says, “Once more unto the breach, dear friends…”

Outside the Honolulu airport, Hawaii is just as delightful as everyone says it is. Thanks to our Mormon ties we didn’t have to go full-tourist. Friends of ours–fellow Mormon-foreigners, a couple where the wife is South Korean and the husband is Japanese—have been living in Hawaii for years and showed us local favourites like a huge old banyan tree hidden off the side of the road, and a strip-mall restaurant serving massive “Hawaiian-sized” slabs of sushi. On Sunday, we wound up at a church service singing from a hymnal written all in Samoan and witnessing a congregation sending off a woman named Celestial to be a missionary abroad.

Outside the Honolulu airport, Hawaii is just as delightful as everyone says it is. Thanks to our Mormon ties we didn’t have to go full-tourist. Friends of ours–fellow Mormon-foreigners, a couple where the wife is South Korean and the husband is Japanese—have been living in Hawaii for years and showed us local favourites like a huge old banyan tree hidden off the side of the road, and a strip-mall restaurant serving massive “Hawaiian-sized” slabs of sushi. On Sunday, we wound up at a church service singing from a hymnal written all in Samoan and witnessing a congregation sending off a woman named Celestial to be a missionary abroad.

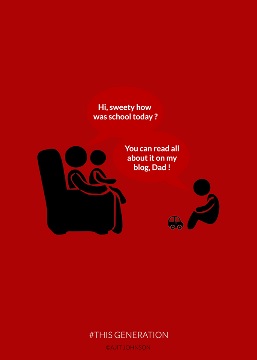

The generation in question isn’t the artist’s own cohort either. From what I can tell, he’s a salty old fella from the beginning of the Millennial spectrum. #THISGENERATION—the one harpooned in his simple red graphics—is that of my kids and current classmates.

The generation in question isn’t the artist’s own cohort either. From what I can tell, he’s a salty old fella from the beginning of the Millennial spectrum. #THISGENERATION—the one harpooned in his simple red graphics—is that of my kids and current classmates. Let’s pursue a methodical close reading of a few of the posters. In this one, #THISGENERATION is hassled for going somewhere private to take pictures of themselves to post in public. Sure, this is a situation that has and will continue to showcase a whole lot of terrible youthful judgment. But let’s hold our noses, take a page out of the gun lobby’s script, and remind ourselves that cameras don’t exploit people, people exploit people.

Let’s pursue a methodical close reading of a few of the posters. In this one, #THISGENERATION is hassled for going somewhere private to take pictures of themselves to post in public. Sure, this is a situation that has and will continue to showcase a whole lot of terrible youthful judgment. But let’s hold our noses, take a page out of the gun lobby’s script, and remind ourselves that cameras don’t exploit people, people exploit people.

but from older people. Most of us won’t commit to long, challenging gamer-ism so we play simple, free, throw-away games like Candy Crush. It’s mostly an old people game.

but from older people. Most of us won’t commit to long, challenging gamer-ism so we play simple, free, throw-away games like Candy Crush. It’s mostly an old people game. I was amused recently to read a twenty-year-old paper warning scholars they ought to take spoken literature (orature) more seriously since it was all #THISGENERATION was going to abide. In the early days of texting, a prominent Canadian author wrote a novel including a vision of the future where both written and spoken communication had morphed into flip-phone era texting shorthand. Of course, that hasn’t happened. #THISGENERATION doesn’t often use their phones as phones. When dealing with people at a distance, they prefer written over oral communication. A phone call means someone’s dead or in jail. #THISGENERATION has become extremely literate, plugging away on Tumblr writing heavy text posts about art and relationships and social justice, learning creative writing in epic style on fan fiction sites, while older adults quip away in 140 characters. No one reads and writes more than #THISGENERATION.

I was amused recently to read a twenty-year-old paper warning scholars they ought to take spoken literature (orature) more seriously since it was all #THISGENERATION was going to abide. In the early days of texting, a prominent Canadian author wrote a novel including a vision of the future where both written and spoken communication had morphed into flip-phone era texting shorthand. Of course, that hasn’t happened. #THISGENERATION doesn’t often use their phones as phones. When dealing with people at a distance, they prefer written over oral communication. A phone call means someone’s dead or in jail. #THISGENERATION has become extremely literate, plugging away on Tumblr writing heavy text posts about art and relationships and social justice, learning creative writing in epic style on fan fiction sites, while older adults quip away in 140 characters. No one reads and writes more than #THISGENERATION.