I’ve been sick. I’m now well-medicated and functioning but I’m still sick-ish after two months—a personal record. It began early this Fall, when in the space of four weeks, I had two colds and one stomping stomach flu. It wasn’t an ordinary bug that razes everything for 24 hours before blowing over. It dragged through an entire week, attacking and then relapsing on all 30 of the people who caught it at our family’s Thanksgiving potluck. My immune system cleared all of that up then opted for something other than its usual return to idling in the bod’s background. Sensing the state of me, maybe—the stress and overwork of preparing for a looming week of PhD qualifying comprehensive exams, my grief at the hard times of some of my loved ones, or tens of thousands of things—my immune system cranked the throttle open, blew me into bedridden bits for weeks.

I’ve been sick. I’m now well-medicated and functioning but I’m still sick-ish after two months—a personal record. It began early this Fall, when in the space of four weeks, I had two colds and one stomping stomach flu. It wasn’t an ordinary bug that razes everything for 24 hours before blowing over. It dragged through an entire week, attacking and then relapsing on all 30 of the people who caught it at our family’s Thanksgiving potluck. My immune system cleared all of that up then opted for something other than its usual return to idling in the bod’s background. Sensing the state of me, maybe—the stress and overwork of preparing for a looming week of PhD qualifying comprehensive exams, my grief at the hard times of some of my loved ones, or tens of thousands of things—my immune system cranked the throttle open, blew me into bedridden bits for weeks.

The world of a sick person is small and terrible. Reading made me feel ill. The to-do list I’d been compiling during the months of exam preparation—catching up on satisfying household projects, overdue time with my kids—all of that was beyond me. Not even my lifelong fix, food, was available. Unable to eat much, I lost about 13% of my weight. (Never congratulate someone on sickness weight loss. It’s just suffering made visible.) But in small worlds, small me, there is still gratitude. As I lay in bed, I was glad to have a bed—a comfortable, warm bed in a safe place. I thought of my ancestors, with the same physical problems I have only trying to rest in cold, damp, crowded cottages without big tubs of running hot water to soak their bones in, and I was grateful.

I was grateful for the kindness of my family, especially my husband, especially when I’m doing nothing to earn it. I wasn’t unkind to him but I wasn’t a very thoughtful partner to him during this illness either, like when I brought him with me to the mother-of-all rounds of blood tests my doctor ordered to rule out every infection he could before putting me on a drug meant to depress my immune system. I forgot that the sound of the vials of blood coming on and off the needle makes my husby woozy, and he didn’t remind me as he stood beside me in the lab, shaky and pale having to hear it all.

Beds and caregivers—in my country, these are considered basic rights of sick people and I’m grateful that these are our collective ideals even though we fall short of them. The next thing I am grateful for is more rare. I’m grateful for spiritual guidance through my illness. While I was sick, we reached out to our faith community and someone arrived at our house with food and treats for my children, friendship, prayer, and what I must acknowledge was true inspiration. I remember our visitor saying in prayer that I needed medical attention. If I was a different kind of person, this advice might have been trite. But I am this kind of person. I am a rundown middle-aged woman with pain, fatigue, bad digestion. When physicians first coined the word “hysterical”, they were talking about me. The inspiration was at once advice and a warning. If I wanted medical attention, I would only get it through insisting, persisting.

The first doctor I saw told me I likely had bursitis in my elbow from leaning on it while holding books to read. He suggested a fancy drug I might not have thought to try myself yet called “Advil.” I cried and begged and he prescribed a stronger pain killer so at least I could sleep. When I ran out of it, I couldn’t bring myself to beg again and I ate the old pills I hoarded from my sons’ wisdom teeth extractions. The hysterical have learned to be resourceful.

The third doctor I saw told me it was just fine for someone like me to give up eating and phoned a GI specialist, talking extremely loudly, announcing my full name, birth date, and current bathroom habits to an emergency room ward crammed with people. This doctor’s medical attention came with a vague insult about my middle-aged figure and a flagrant lack of regard for my dignity and humanity. But heck, it was nothing more than I deserved for following the advice of my second doctor, my family doctor, and clogging up the ER, desperate to make an end-run around the appointment desk of a specialist’s office by gambling on seeing one in the hospital clinic. The maneuver failed and I was sent home with an assurance someone would call me with an appointment. Still waiting.

By this point, medical attention had been awful and useless. It reduced me to something mewling, dirty, sneaky, superfluous—a noisy waste of time and space. Make way for a baby with a rash, a guy who dropped something on his foot. The hysterical’s fight for medical attention can be hopeless–painful, please stop paying attention to me. I don’t want any more. I’ll go.

Truly, I would have quit and gone home to bed, given up on the life I used to think I’d have, if it weren’t for the confidence I had in the spiritual guidance I’d received. This kept me hounding the clinic until my family doctor, working outside his professional comfort zone, found the confidence of his own to prescribe the medicine I need right now. Confident is the opposite of hysterical. The spiritual provides a vantage point to see “things as they really are” rather than things as a lifetime of systemic bias against us can dupe us into accepting. Do not accept it. You need medical attention. You are worth it. Carry on.

The world of book marketing is fairly straightforward: the more money a book has behind it, the better it tends to sell. Does that sound cynical? Maybe, but it’s also evident in industry practices like giveaways for newly released books on the Amazon-acquired mega social network for readers, Goodreads.com. Not that long ago, during the heavy marketing phases of my first two novels, anyone could post a book giveaway on Goodreads and hundreds—hundreds—of people would see that book, look at its cover and title, read its synopsis, maybe even the author’s name, and add the book to their to-be-read list in exchange for getting a chance to win a free copy. All it cost publishers and authors, big or small, was the wholesale price of the book, and postage. But by the time my third novel was published, Goodreads was charging hundreds of dollars to give away books on the site. Isn’t that nice? It’s great to see big, well-funded enterprises sticking together.

The world of book marketing is fairly straightforward: the more money a book has behind it, the better it tends to sell. Does that sound cynical? Maybe, but it’s also evident in industry practices like giveaways for newly released books on the Amazon-acquired mega social network for readers, Goodreads.com. Not that long ago, during the heavy marketing phases of my first two novels, anyone could post a book giveaway on Goodreads and hundreds—hundreds—of people would see that book, look at its cover and title, read its synopsis, maybe even the author’s name, and add the book to their to-be-read list in exchange for getting a chance to win a free copy. All it cost publishers and authors, big or small, was the wholesale price of the book, and postage. But by the time my third novel was published, Goodreads was charging hundreds of dollars to give away books on the site. Isn’t that nice? It’s great to see big, well-funded enterprises sticking together. I am not going to post a photo of someone else’s writing today.

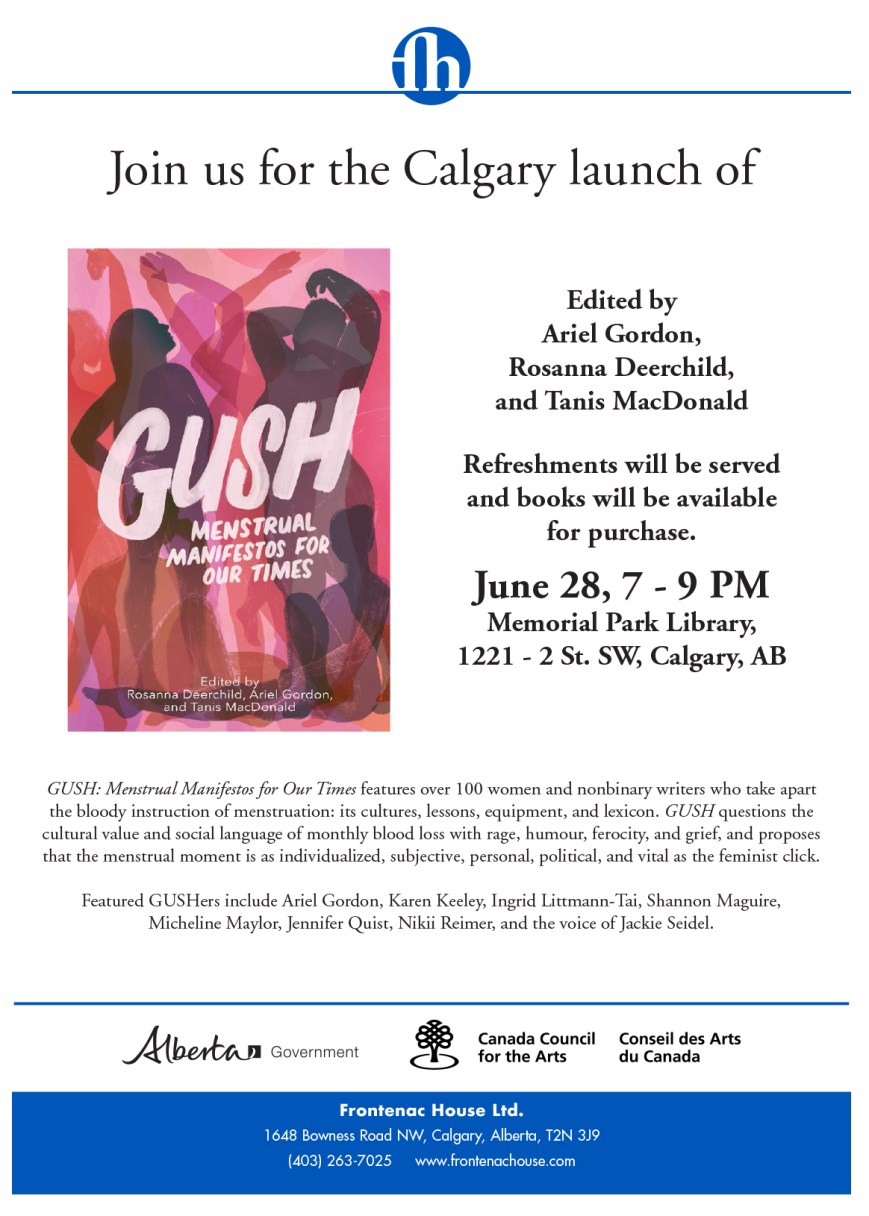

I am not going to post a photo of someone else’s writing today. Catch me in Calgary on Thursday 28 June as I help launch Gush: Menstrual Manifestos for Our Times. It’s a new anthology from Frontenac House edited by Rosanna Deerchild, Tanis MacDonald, and Ariel Gordon. My contribution has a laugh at how I can answer the old timey cliched question of whether I thought I was dying the first time I got my period with “No, I thought I was getting my period the first time I was dying.” Trust me, it’s funny.

Catch me in Calgary on Thursday 28 June as I help launch Gush: Menstrual Manifestos for Our Times. It’s a new anthology from Frontenac House edited by Rosanna Deerchild, Tanis MacDonald, and Ariel Gordon. My contribution has a laugh at how I can answer the old timey cliched question of whether I thought I was dying the first time I got my period with “No, I thought I was getting my period the first time I was dying.” Trust me, it’s funny. One of the nicest compliments I have ever received was from a friend I saw every day, for hours at a time, for an entire month, who told me I was the happiest person she knew. Great compliment. Hearing it made me even happier. That’s what compliments are for. That’s how it’s done.

One of the nicest compliments I have ever received was from a friend I saw every day, for hours at a time, for an entire month, who told me I was the happiest person she knew. Great compliment. Hearing it made me even happier. That’s what compliments are for. That’s how it’s done. personal about me than mere gender. I inherited my grandfather’s face, a certain kind of Irish face which I love on him, on my baby brother, on my ginger nephew and on my middle son to whom I passed it along, but which doesn’t play so well on a woman’s head. On me, Granddad’s wise and trustworthy expression plays as nasty and not trying hard enough. Ever since my grade six teacher first complained about it to my mother, men and women who do not know me will sometimes stop me to let me know my sad-looking-not-sad face is a problem for them. There is always something of an assertion of power in these comments but I do allow that they are usually also meant as a sort of overbearing kindness—as if their special insight will liberate me.

personal about me than mere gender. I inherited my grandfather’s face, a certain kind of Irish face which I love on him, on my baby brother, on my ginger nephew and on my middle son to whom I passed it along, but which doesn’t play so well on a woman’s head. On me, Granddad’s wise and trustworthy expression plays as nasty and not trying hard enough. Ever since my grade six teacher first complained about it to my mother, men and women who do not know me will sometimes stop me to let me know my sad-looking-not-sad face is a problem for them. There is always something of an assertion of power in these comments but I do allow that they are usually also meant as a sort of overbearing kindness—as if their special insight will liberate me.

Maybe you don’t feel like reading a book right now. I understand completely. Fortunately, reading isn’t the only way to experience a story, especially if it’s full of music and pictures. And so we bring you a bit of a playlist from my newly released novel,

Maybe you don’t feel like reading a book right now. I understand completely. Fortunately, reading isn’t the only way to experience a story, especially if it’s full of music and pictures. And so we bring you a bit of a playlist from my newly released novel,