My son says this Fever Ray video reminds him of me. Is it the hair, the skinny legs, or all the going off to do weird stuff by myself?

I’m in a thrift store with my sixteen year old son. (Anyone who doesn’t have a sixteen year old son should get one someday. It’s kind of like having a stupid, darling high school boyfriend again only without all the icky tension.)

We get to the furniture section of the store – the part set-up like a dozen crummy little living rooms butted against each other.

“It’s like some old grandpa’s house,” my boy says.

And then, as I often can, I track of his train of thought. It’s passing through the stop called “grandpa,” chugs in and out of the station called “the only dead person I know well” before it screeches to a halt in the busy rail yard labeled “death.”

“This is where they bring people’s stuff after they die,” my boy says.

“Yup,” I agree. “This is where you’ll bring my stuff after I die.”

He doesn’t choke or get maudlin but he does say, “I won’t bring your stuff here. I’ll keep it. I’ll take your computers and find everything you ever wrote and print it out and save it.”

I tell him he’s sweet and we leave the store, bound for another thrift shop. So far, we’ve bought a 1970s era Charlie Brown paperback and a discarded copy of a book I contributed a couple of essays to but we still haven’t found the t-shirt with the graphic of a killer robot with a Korean speech bubble that will be my son’s find of the day. We get into the car, tune the radio to one of our favourite CBC shows – the one I work for a few times a year, – and we back into the Saturday afternoon traffic.

See it? My life – including my life as a writer – forms a part of my son’s life. It’s something he sees as enduring and inseparable from the imprint I leave on the world he is in the process of inheriting from me.

A recent article in The Atlantic entitled “The Secret to Being Both a Successful Writer and a Mother: Have Just One Kid” assumes motherhood and a stellar career as a writer are irreconcilable competing interests. The article’s hook of a headline (which was was not written by the author, Lauren Sandler), is beside the point. This isn’t so much a piece about family size as it is about the level of personal investment it takes to write for a living. On its way, it looks at mother-writers like Susan Sontag and Joan Didion to examine whether these women’s single-child families are the compromise that made it possible for them to excel at their careers while raising children – er, a child.

Of course, there are writers who do have more than one child and Sandler suggests that some of these women preserve their careers by hiring someone else to look after their kids. Her other suggestion is that women writers can thrive in families willing to invert traditional gender roles and cast men as their children’s primary caregivers.

Sandler doesn’t seem convinced that any of these strategies is necessarily enough to transform an artist into something considered a good parent. The article presents examples of writer-mothers being absent, self-involved, and dismissive – sending their lone children away with “Shush, I’m working.” By the end of the piece, it’s acknowledged that there’s a difference between motherhood and “momish-ness” and artists often set the latter aside.

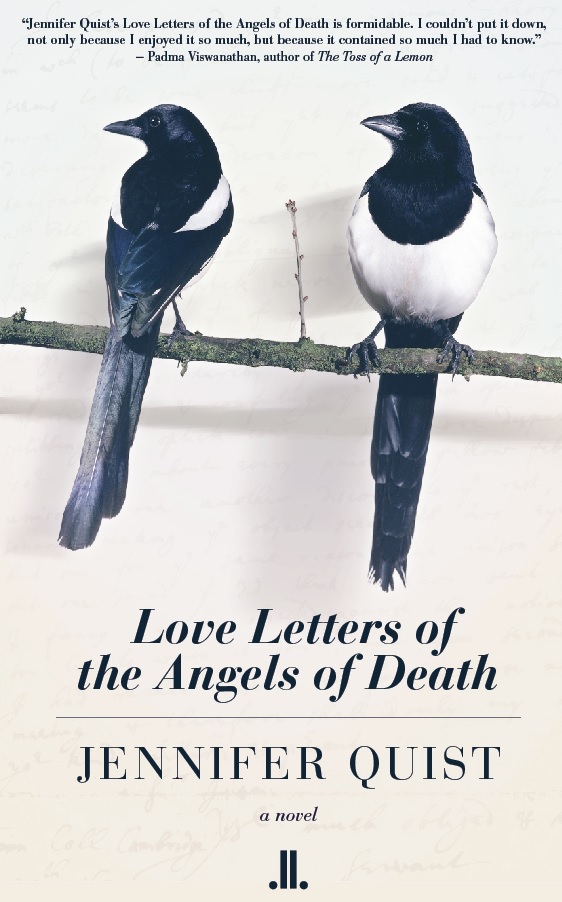

Right now, weeks before my debut novel is even released, I’m not what The Atlantic would consider a successful writer. But I’m still free to fret over my own experience raising five children while writing. Am I devastatingly dismissive? Am I “momish?” Do I have to be?

I admit I’m missing some of the traits of momish-ness – especially in the kitchen. If my sons want cookies, they bake them for themselves. I might make something special on holidays but I always garnish it with demands for praise and thanks. “Hey, I made cookies. Aren’t I good? Look at how good I am.” Honestly, I don’t even cook dinner very often. My husband usually does that, without complaint, after a full day of demanding non-domestic work.

But is neglecting cooking enough of an an explanation? Why do I still get prickly when I’m asked how I find time to write? No matter how kindly it’s meant, the question seems to imply neglect and self-centredness – a lack of understanding of my own situation that misleads me to believe I can do two incompatible things at once. I must be either willfully negligent of my kids or witlessly oblivious to reality.

Sometimes, I do put my kids off with my own version of, “Shush, I’m working.” But there are reasons why being shushed by their writer-mother isn’t a developmental disaster:

1) When my sons leave home, they will not be met with people who jump to satisfy all their wishes for food, attention, money, housekeeping, technical support, etc. If I raise them to expect instant service, I do them and the other people who will live and work with them a disservice.

2) By ignoring traditional areas of housework, I help the boys see distinctions between housewifery and motherhood. They are not the same, they are not the same, they are not the same…

3) Because I work inside the house where my kids’ lives are centred, they get plenty of “quantity time” so there’s not as much need to orchestrate fancy “quality time.” I don’t arrive in the house as a celebrity here for a limited engagement. I’m not a special attraction so I can relax and forgo behaving like one.

4) All mothers have interests that eat up time they could spend with their children. It might be paid non-writing work, making fancy scrapbooks, training for marathons, stoking reality television habits — anything. When it comes to maternal attention, my kids aren’t that different from anyone else’s.

5) My sons are not strangers dropped here at random. They’re very much like me. They are writers, artists, and creative people themselves. Maybe they understand better than other people the importance of this kind of work. They know it makes me happy because their own similar projects make them happy. Maybe my self is overbearing enough to convince them to value in themselves what I value in myself.

The self – that’s the core of the problem I have with Sandler’s approach to writer-mothers. She writes of our need to “negotiate a balance between selfhood and motherhood.” I don’t know how these two -hoods could be separated, let alone set on opposite sides of a scale and balanced. The self is far more like a casserole than a bento box. (Hey, it’s a cooking simile – aren’t I good?) Motherhood hasn’t effaced my self but it has been integrated into it. A healthy self is a pliable one, not a brittle one. It’s dynamic and able to accept how impressionable it is to powerful forces including – or especially — kids.